When working with containers, especially in Kubernetes, it’s common to troubleshoot network issues or communicate with other services from within a POD. For most engineers, the go-to tools for these tasks are often BusyBox utilities like telnet, curl, nc or wget. However, there are scenarios where BusyBox isn’t installed in the POD, and you find yourself without these essential networking tools.

Related video:

But don’t worry—if your POD has bash installed, there’s a lesser-known method you can use: /dev/tcp. This built-in feature of bash allows you to perform basic network communication tasks directly from the command line.

The Role of BusyBox in a POD

BusyBox is a popular suite of Unix utilities that provides stripped-down versions of common commands. It’s widely used in containers because of its minimal footprint. With BusyBox, you get access to a variety of tools, including:

telnetfor simple network connections,wgetandcurlfor making HTTP requests,nslookupordigfor DNS lookups.

However, if your POD image is extremely minimal or designed for a specific purpose, BusyBox might not be included. This leaves you without the usual arsenal of network troubleshooting tools.

Enter /dev/tcp: A Hidden Bash Gem

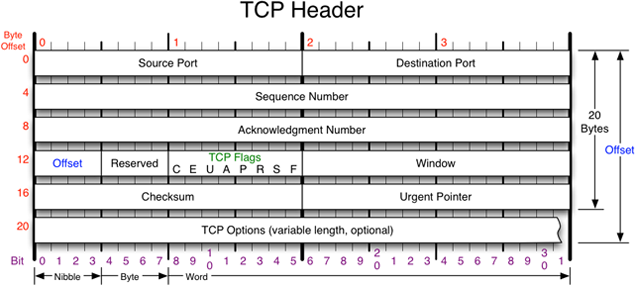

If you’re stuck without BusyBox, and you have access to bash, you can still perform network operations using the special file /dev/tcp. This feature is available in bash versions 2.04 and later, and it provides a way to make TCP and UDP connections directly from the shell.

How /dev/tcp Works

The /dev/tcp file isn’t a real file on disk—rather, it’s a special bash feature that lets you open a network connection and send or receive data. The syntax is straightforward:

cat < /dev/tcp/<hostname>/<port>This command attempts to read from a TCP connection to the specified hostname and port. You can also send data by redirecting output to /dev/tcp:

echo -e "GET / HTTP/1.1\nhost: <hostname>\n\n" > /dev/tcp/<hostname>/<port>Examples of Using /dev/tcp

Let’s explore a few practical examples of using /dev/tcp inside a POD:

1. Checking if a Port is Open

You can use /dev/tcp to check if a specific port is open on a target host. This is similar to what you might do with telnet or nc:

if echo > /dev/tcp/google.com/80; then

echo "Port 80 is open"

else

echo "Port 80 is closed or unreachable"

fiThis command attempts to send data to Google’s HTTP port (80). If the port is open, the echo command will succeed, otherwise, it will fail.

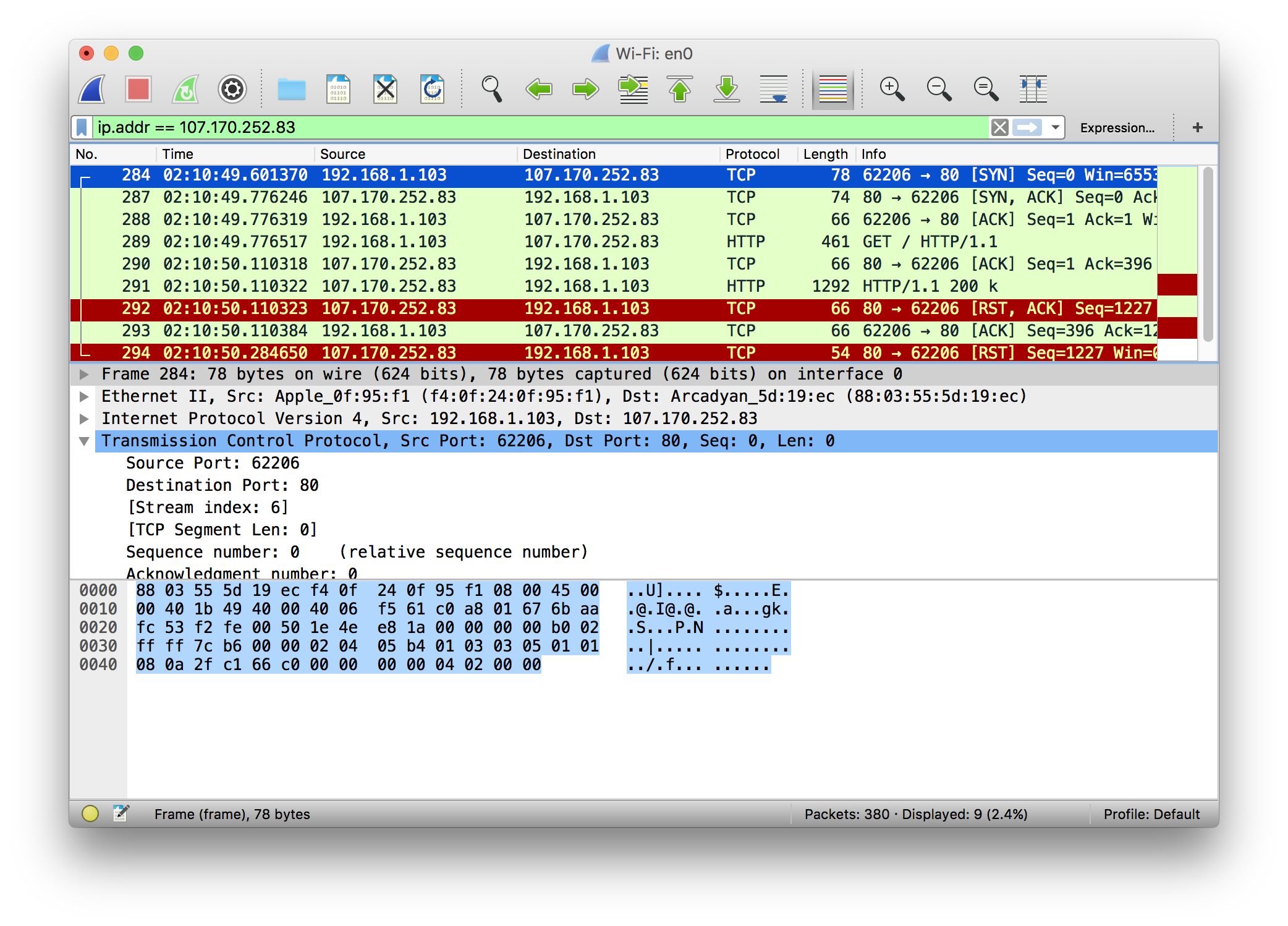

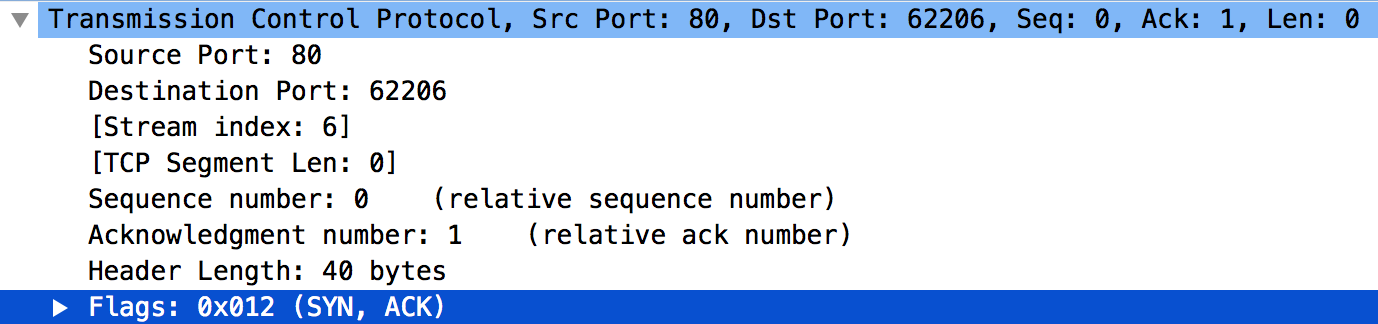

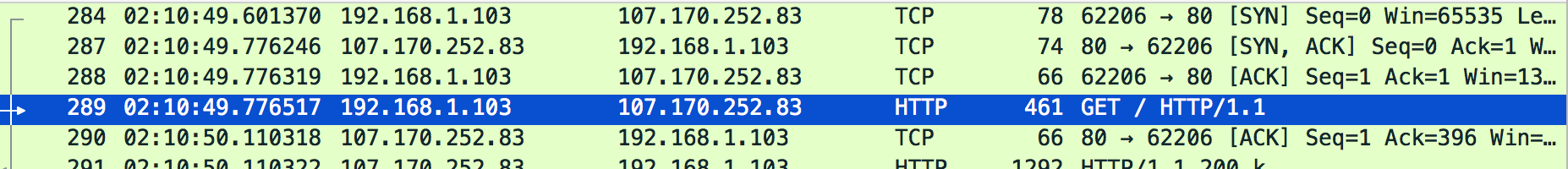

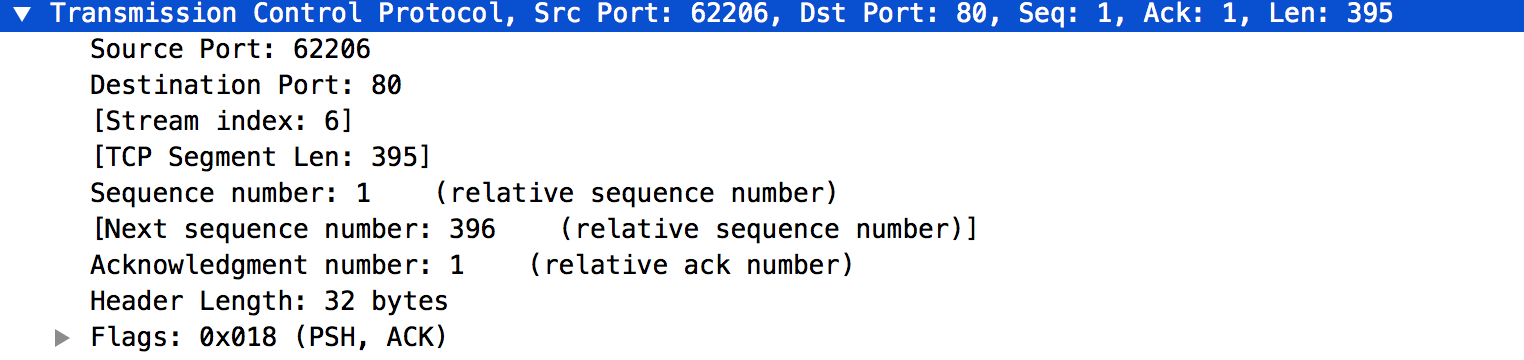

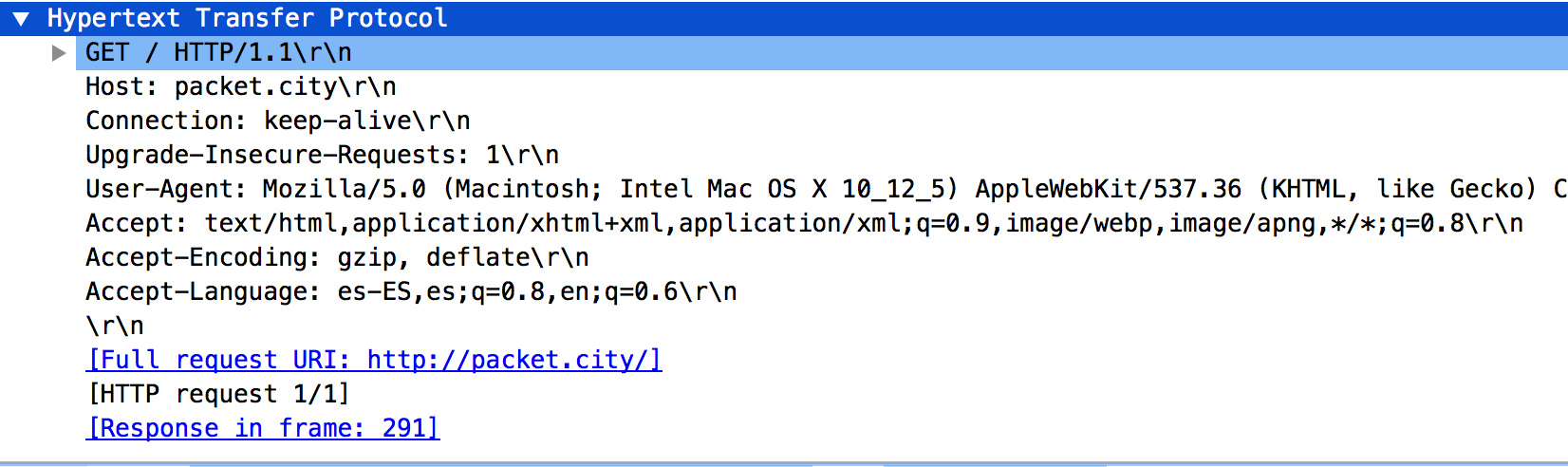

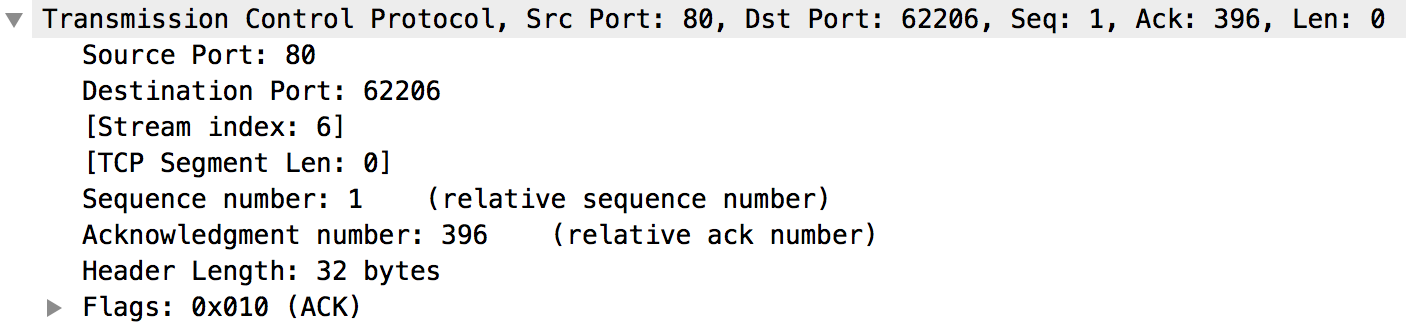

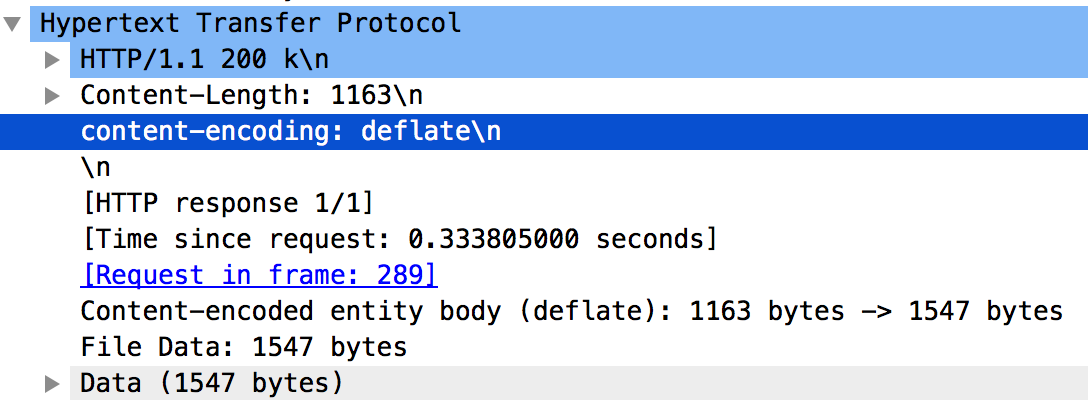

2. Performing a Simple HTTP GET Request

Without curl or wget, you can still make HTTP requests using /dev/tcp:

exec 3<>/dev/tcp/example.com/80

echo -e "GET / HTTP/1.1\nHost: example.com\nConnection: close\n\n" >&3

cat <&3

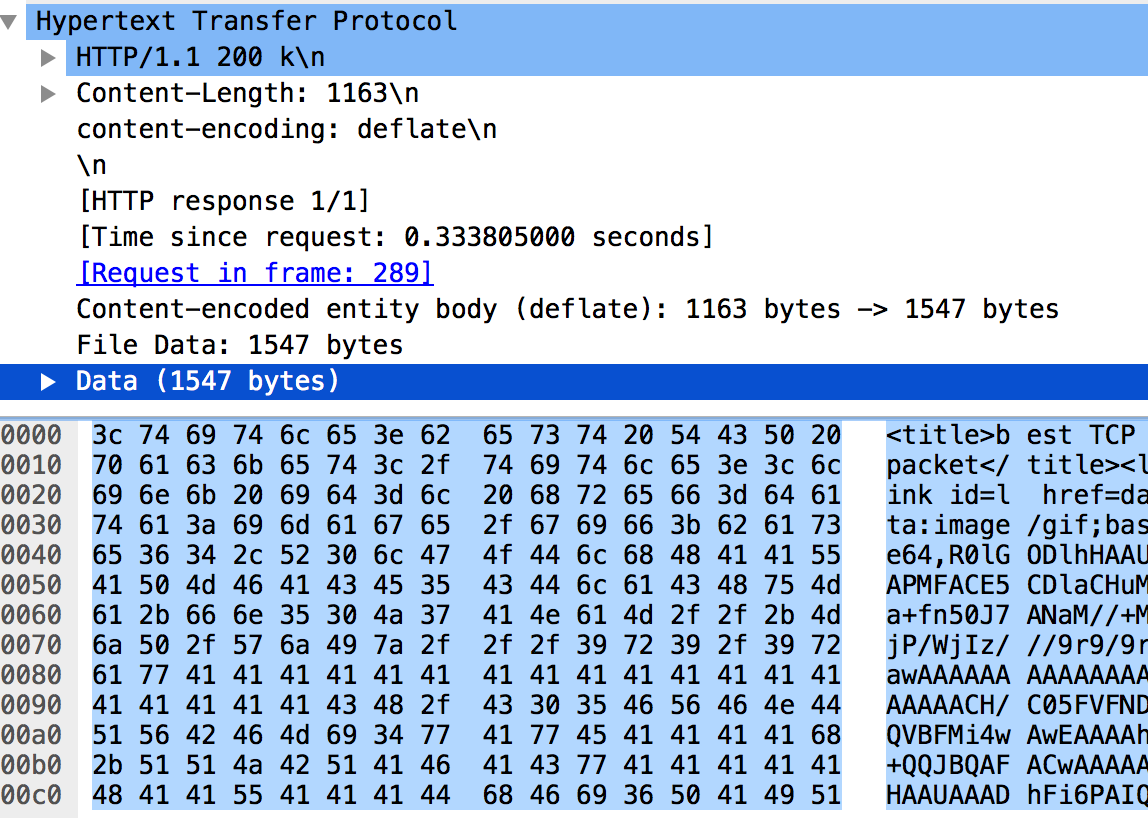

exec 3>&-Here, the exec 3<>/dev/tcp/example.com/80 command opens a TCP connection to example.com on port 80 and assigns file descriptor 3 to it. The echo command sends an HTTP GET request to the server, and the cat command reads and displays the response.

3. Basic DNS Query

You can use /dev/udp (a similar feature for UDP) to perform a simple DNS query:

echo -ne "\x01\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x07example\x03com\x00\x00\x01\x00\x01" > /dev/udp/8.8.8.8/53This sends a raw DNS query to Google’s DNS server (8.8.8.8) asking for the IP address of example.com. Interpreting the response requires more work, but this example shows how you can interact with network services at a low level.

Conclusion

While BusyBox is a fantastic toolset for handling networking tasks inside a POD, it isn’t always available. In such cases, knowing how to use /dev/tcp can be a lifesaver. This built-in feature of bash allows you to perform basic network operations, such as checking open ports or making simple HTTP requests, without relying on external utilities.

Remember, though, that /dev/tcp is not as user-friendly or powerful as tools like curl or wget. It’s best used as a fallback option when you’re in a minimal environment and need to troubleshoot connectivity issues.

By mastering these lesser-known tools, you can be better prepared for any situation that arises within your Kubernetes environment.